Table Management — On Recruiting Players, Setting Expectations, Investment & Feedback

Estimated Reading Time – 51 minutes

Photo from Pexels (CC0)

Introduction

Before I touch on this topic, I am going to impart some life advice that I promise is relevant to the matter at hand.

The most important thing is to always irreverently be you. When people walk away because they do not like who you are, that isn't some standard you need to conform to in order to avoid alienating those people. That's the trash taking itself out.

We unfortunately live in a world where many people can't comfortably be who they are in a lot of places, but this is still good wisdom in many situations – if you have to change the way you act or are around someone else in order for that person to be your friend, are they really your friend in the first place? Is it you that person is friends with, or the persona you've conjured for yourself? Do you even want to be friends with them?

It goes both ways too, of course it's possible that what you do genuinely alienates people, and some are going to be fine with it and others aren't. But other people will also appreciate that you're honest and upfront about who you are. I'm sure at some point you've felt glad that someone showed their true colors early, and that doesn't always mean they're a bad person necessarily, just that you're not compatible, and that's okay.

In a way, it tends to save a lot of confrontation, feelings of betrayal and feelings of friendships slipping away as you feel that you're having to put up a brave front to maintain communication, and losing motivation to do so. We could all use a little more honesty, in general. And this extends to a lot of things in life – TTRPGs are one of them.

In Search of Answers

Often I see GMs lamenting that players seem distant.

They don't take notes, they don't keep track of events, they have little understanding of their own sheets or the rules, they don't contribute or input feedback after a session, they neglect handling level ups or shopping between sessions, they arrive at session start time but then wanna chat for 30 minutes, among loads of other things.

Many times, when I try to talk about these things with people, they get very stuck on the why, looking at these issues in isolation from each other. I hear sentiments along the lines of “Did I do something wrong? Are my stories not interesting? Are my encounters too boring?” in search of some inner truth regarding lack of feedback, lack of engagement, lack of punctuality, all of the above or other.

At best, this is a narrow view of the problem they're facing, and at worst leads to terrible spirals of de-motivation regarding an otherwise fantastic hobby.

The true issue is all of these are one shared issue plagued by lack of communication, which in itself is fairly clear, but the crux here I'd say isn't actually why, but when. When did you stop communicating? When did they stop being invested?

Almost always, in situations where I've been faced with this question, and when helping others work through it, the answer is simple – right at the start. In fact, a lot of times, that wouldn't even be an accurate descriptor – many times the answer is that there never was any investment or communication in the first place.

A bridge of mutual understanding was never actually made for what everyone involved wants out of a game, and this has damaged the enjoyment of everyone at the table. It's critical to note that everyone at the table is important for the game's success, and everyone's enjoyment of the game is relevant. People seem to tend to forget this includes the GM.

People parade the concept of a Session 0 as exactly that, but I would argue that it really isn't. At that point, you have already sat at the table with the agreement that you are playing the game without setting any form of expectation – the damage is done. By the time most tables host Session 0, Session 1 is already marked on the calendar, and probably on next game night's date, too. A little late for going back to the drawing board and grabbing someone new if things don't align.

I absolutely agree that Session 0 is an excellent resource, but it's being used for the wrong purposes.

I also often see people saying that “if your players are happy, you're fine”, but this encourages an attitude of self-sacrifice for someone who already most probably feels unrewarded and like they're the only one really contributing at the table.

That's not to say that you should simply discard any opinion that doesn't line up with your own, the players enjoying your game does matter. But if you're not having fun running it, what's the point? You shouldn't force yourself to do something you don't enjoy in your free time – free time that you're supposedly dedicating to a hobby out of passion.

Curating Your Table

Every time I see an RPG horror story be shared on social media regarding an online game, I can't help myself but to take a peek at that user's profile to see what the recruitment post looked like, and every time it's exactly what I expected.

There's never any filter.

People post on websites looking for players, with long-winded explanations of their setting, the levels the campaign will span, all kinds of crazy ideas they have for the plot, and completely neglect to mention what their GMing is going to be like. What the game is going to actually entail in terms of the substance of playing it. What type of players they are looking for.

Sometimes, when told that maybe they should consider doing something about it, I see people respond with “but if I were to put a Google Forms or something for people to sign up on, no one would do it”, or “if the Google Forms I do have were any longer, no one would bother completing it!”

Well, as someone who GMs and plays, I can tell you at least I would. But I'll also tell you something else.

Your average table plays 4 hours per session, a session a week. That's 4 sessions a month for 12 months in a year. That's 192 hours a year of content you are producing for free. With many modern games having about a ~5 hour runtime for their story (excluding RPG-flavored senseless grinding and padding) that's about 39 games in length.

Except as a GM, you're likely to spend at least an equal amount of time thinking about and preparing the game outside of session. Even if you were to only spend an hour on prep between sessions – which let's be real, is a generously low amount – that's still an additional 48 hours for a total of 240. Make that 48 games in length now.

With the recent price hike in games to a 70€ standard, that's 3360€ worth of time in entertainment you are creating for your players a year, effort-wise, minimum. For those of you thinking “well my game doesn't have the polish of a AAA game, either”, how about AA at 40€ for a total of 1920€? Standalone indies in the 20€ range for a total of 960€? How much do you value – or maybe unfortunately don't value – your time and effort?

And this where I go back to my original advice. When you're spending so much time and passion on something with so much creative value, is the type of player you want really the one that can't be bothered spending 5 minutes filling in a few questions for a form?

At the end of the day, campaigns are a communal commitment, sometimes a years long one, with lots of ups and downs. People will run into scheduling issues, not every session will be the most exciting one. If at the prospect of joining a game – which should hopefully be something a player actively really wants to do – they can't bother to put any effort in... Well, you should know what to expect, and it frankly shouldn't be a surprise.

Filters Aren't Just Gatekeeping

(And Not All Gatekeeping Is Sheer Elitism)

My advocating for filters for sign ups isn't for promoting some kind of high-effort elitism of enthusiasts-only tables. They're not for “filtering out the casuals.” They are just as useful for filtering out players that are too invested compared to the table.

TTRPGs are, as they say, operated by vibes.

It's important for everyone at the table to be on the same wavelength. Sticklers for the rules and high-investment players probably won't mesh well with beer-and-pretzels players who are just there to roll some dice and do whatever independent of the rules, and this isn't because either of them is playing wrong, it's just that they probably shouldn't be put together.

There's certainly many GMs that might read up to this part and think “I don't think it's that bad, my table just kinda does whatever”, and that's awesome! I'm glad it works out for you, but that means that you're probably playing with players that are okay with just doing whatever.

But it can be really easy for more niche enthusiasts for systems, especially people that hang out in TTRPG spaces to discuss design – who happen to be more likely to GM – to be strong-armed into 'doing whatever' by players that aren't as invested, in the same way that rules lawyer players can strong-arm a game of less system-invested players, and the result for both is disastrous. Yet I only ever see one of these two get talked about.

Nonetheless, filtering can still be useful for you if you are a more laidback GM precisely for filtering out rules lawyers, too. The central point of this is that filtering allows you to curate a table that matches your GM style, and who are all there to participate in a communal activity with a shared goal and similar energy. It goes both ways.

This isn't just for GMs either, but also for players. In the same way that a GM can be disappointed when players don't meet their expectations, if a player goes into a game with no expectations given, they are likely to make their own, and be disappointed when these aren't met.

And when it reaches this point, if you already had no communication before, you likely have negative communication now, and that's where so many of these stories seem to start. But that's not where it started, not at all. It started long ago, you just missed it.

They say there's a player for every table and a table for every player, and I agree. But that's exactly why we shouldn't necessarily be so flexible – to our own detriment, no less – with our play styles. That's not to say we should be tyrannical, draconian or incredibly rigid with what we do, but it's important to note the points I'm making aren't just about GMs doing a disservice to themselves.

It's also about doing a disservice to players at the table that maybe aren't getting much out of it and could have a better time elsewhere, and to the players out there that would be a great fit but aren't at your table as you keep chugging along a game where no one seems to want to pitch in the same level of effort as anyone else – whether that's higher or lower.

Because it really doesn't end at the GM – players who are more invested will find themselves at a table where no one shares their enthusiasm for planning, theorizing and plotting, and that's severely discouraging. Equally, more casual players will feel that those players get too stuck in planning and plotting and grind things to a halt, and no one's happy.

Of course a healthy balance is important, a table of overthinking players is likely to take long at every junction when a decision must be made, and a table of players that don't think will run head first into every bad decision. Both of these can be fun – and if that's the experience you want, then curating your table allows exactly that! – but for your average table you're probably looking at wanting a bit of both.

“But that's bad right? Earlier you said the two probably shouldn't be together.”

Well, no, not exactly. I said less-invested players and over-invested players should probably not be together, but that doesn't mean you can't have less-invested players that think things through when they do participate or over-invested players that constantly pitch in but fail to take things into account. Investment isn't only about system mechanics or knowing things, but effort and participation in adding something to the table.

What matters is that the level of effort put forward, and the enthusiasm and investment in the game in wanting to participate and pitching in their perspectives and unique assets at the table is at a similar level – for invested players that come up with silly ideas to have those ideas expanded upon by other invested players with more tactical knowledge, and have back and forth conversation between invested characters, or a table where people are more casual to have the occasional moment of strange deep wisdom uttered by the party member you'd least expect in the middle of their casual dice-rolling adventures, left to hang in the air.

It's when you have a thoughtful character who philosophizes in a table with no patience for it, or someone who rushes headlong into danger and ruins the careful plans of the remainder of the table, that you have a problem. But if they swapped tables with each other, they'd probably be happy.

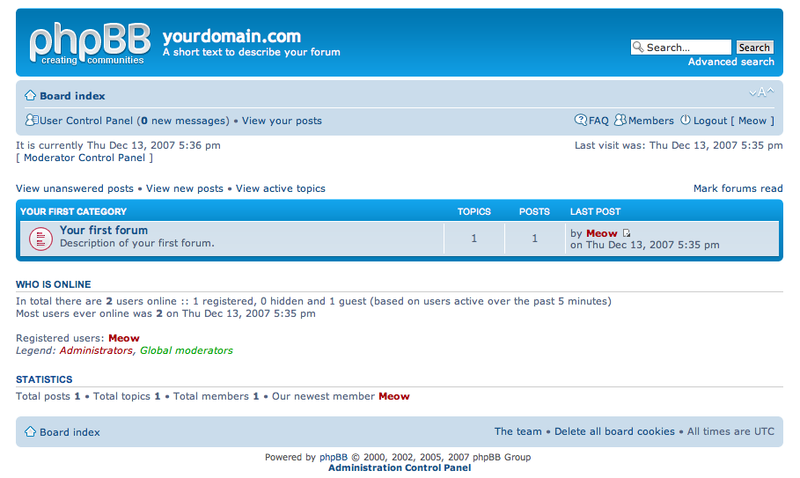

I remember in the early 2000s those now-ancient phpBB forums for TTRPG discussion and play-by-post games, and the laundry list of rules you'd have on sign-up – many that to this day we take for granted. I remember the strict sign up verification and approval process. It was definitely a pain.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons (GNU GPL)

But a consequence of just how curated those communities and games were was the quality of them – whether that was absurdly random games with no rules, or strictly-serious heavily arbitrated ones. Everyone who put in the effort to be there did so because they wanted to, and had a similar level of enthusiasm. Some of those games felt life-long, and I'd wager many are still going to this day because of it.

Earlier in this post I said this:

If you have to change the way you act or are around someone else in order for that person to be your friend, are they really your friend in the first place? Is it you that person is friends with, or the persona you've conjured for yourself? Do you even want to be friends with them?

And that's still true here. If you have to severely change the way you run a table to satisfy your players, is it really your table they want to play at, or the idea they have of your table?

Although ideally these two should align, even at a good ('Good' here meaning fitting for the game you're running, of course) table these might differ slightly – and it's okay to be flexible – but if even after all that effort you go through to meet those differences in the middle they still can't reciprocate, do you even really want to run that table after all?

This isn't me saying that you should dissolve the table you're running right away if you're unhappy. Touching base again can help resolve things, asking if people really wanna keep going with the game or not and pressing for answers beyond shrugs and “yeah, sure” can be helpful, but it's okay if the answer is a “no”, or if the answer is indifference or “not really but then I'd have to find another table” and you're not okay with that.

What's not okay is turning something that is supposed to be a passionate hobby into burning yourself out meeting standards that have been unfairly placed.

This isn't even really anyone's fault in particular, not the GM for not filtering necessarily, nor players for continuing to play as they do despite the table. It all circles back around to being a misunderstanding born of lack of communication and setting expectations, and I think many tables would be far healthier if people were less afraid of being honest and owning up to when a game just isn't for them on both ends of the table.

The same way that you probably have friends in real life, no matter how close, that you'd play certain games with and invite to certain events, but not others, it's okay to make that same distinction here. People generally think every game is a game, and if you play it then that's that – but the truth is that the way you play the game changes how the system expresses itself a lot.

Some people might enjoy those expressions more or less, and that's okay. “I like basketball, but I'm more of a three-point contest kind of guy when it comes to playing” is a valid statement, and so is “I like [TTRPG], but I prefer my tables with [more/less/no] [combat/roleplay/exploration] when it comes to playing.“

You're still a player of that system, you just like something else. But one shouldn't assume that every player of that system likes the same things. Preferences are valid, and you shouldn't feel pressured to not express them or conform to the expected standard unless you want to. Be honest, both as player and GM.

But, such as it is, it wouldn't be a post from me if I didn't talk about a solution beyond just the problem itself. So here's some things to consider when you next prepare to run a campaign – if you already have a filtering method for your posts, consider this a chance to analyze it critically, and see if it meets the criteria you want it to.

Searching For Players

Part I — Be Honest & Thorough

The first step is to be honest. Be honest not just with your prospective players, but with yourself. Before you begin planning your player search, perhaps before even planning the campaign you're looking for players for, ask yourself a few crucial questions regarding the basics. Here's a list of some simple questions I use that form the backbone of the process.

- What am I hoping to do with this campaign?

- What genre or general vibe am I going for?

- What themes am I hoping to explore?

- How do I want to balance the three pillars of TTRPGs?

- How much effort am I hoping to put in?

- How long am I expecting to spend preparing each session?

- How much effort am I expecting the players to put in?

- How long do I want this campaign to go on?

The answers to these questions don't have to be long-winded, but how simple or complex the answers themselves are can also be valuable information about what you're expecting from the campaign as its GM. Remember that we're here to settle expectations, and that doesn't just go for players. Knowing more about what you expect of the table and game will make it much easier to communicate these things with others.

If you're currently planning or running a campaign and find yourself unable to answer some of them, think about why that might be, and the implications it might have for your game – both good, bad, and everything in between.

Analyze these thoughts, and what your answers are for them. See how your answer to each one might make you think and go back to change the answer of another. A clear creative vision isn't just conducive to finding a better fitting table for your game, but for a better, more well-directed campaign, no matter the table.

Once you've reached a sense of self-understanding and some level of finality regarding these thoughts, you can start looking into formulating them into something tangible for a looking-for-players post. Which brings me to the next part of this section – be thorough.

Now that you know what you want out of your campaign and the table that will play it, be upfront about your intentions and what you're hoping for. Cover all the things you feel are relevant, and communicate all the expectations you've established previously.

If there's anything that might turn people off from your game, then be even more explicitly upfront about it. Those sorts of things, like NSFW content, references to racial issues, slavery, and other topics of that nature won't get any more digestible just because you obscure them in the post.

Hiding those things only makes your vetting process harder, as you're likely to have people join, find out, and leave, forcing you to look for new players once again – or worse, they stay, despite being uncomfortable, and the table vibe is affected because of it. Being upfront about things that may make others uncomfortable is beneficial to everyone.

If there's anything that you expect from players, game-related or not, that might make people uncomfortable, be honest about that too. Being LGBTQIA+-friendly, taking notes, using a microphone or camera, and whatever other things you expect, putting that upfront where it'll make someone uncomfortable if they aren't interested in meeting those standards is the easiest way to filter out people that, for any reason, you wouldn't want at the table anyway.

With that established, here's a template I refer to when preparing to post a listing for a game:

Time: [Timezone if looking to set schedule/Schedule if game is on-going] Platform: [Foundry/Play-by-Post/In-Person/etc] Requirements: [Microphone/Camera/Good Connection/Decent Hardware/etc] Genre: [A summary of the genre or general vibe the game fits into.] Variant Rules: [If any are present. For Pathfinder 2e, things like Free Archetype, Ancestral Paragon, or how to rule Recall Knowledge.] Me as a GM: [A summary of how I like to run the game regarding rules, homebrew, storylines, etc.] You as a Player: [A summary of some general expectations I have regarding taking notes, participation, knowing your sheet, etc.] Player Total: [How many players you're looking for for the table, or how many spots are free in a pre-existing one.] Summary: [A summary of the concept and plot of the campaign, the general vibe I envision for the table, some elaboration on what I'm looking for, any extra details, and a space for a technique I'll elaborate on later.] Sign-up Sheet: [Link to a Google Forms or some other form of data-gathering filter.]

While not perfect, this should simplify topics that make it easier for a player to think through and decide if they are a good fit for your table and if yours is a table they're interested in playing in. That way, anyone whose request to join reaches you is someone that you at least know, at worst, wasn't turned off by the game you're proposing to run, and at best is someone who actively aligns with it.

But of course, this only works – and you can only have that guarantee – if you have any measure of certainty that the player signing up for your game actually read the post.

But you can't possibly be certain they've read it, it's not like you're there watching them.

Well, not necessarily. Let's go back to that one little technique I mentioned in the summary field of the template I showed you just now.

The Brown M&M Clause is, succinctly described, a method of doing exactly that. By placing a small, innocuous and effortless instruction amidst our long-winded summary in the template, we can ensure the people who we receive sign-ups from have actually read our post.

Consider this:

Summary: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Faucibus nisl tincidunt eget nullam non nisi est sit. Placerat duis ultricies lacus sed. Metus vulputate eu scelerisque felis imperdiet proin fermentum leo. Lacus luctus accumsan tortor posuere. Vitae auctor eu augue ut lectus arcu. Volutpat sed cras ornare arcu dui. Sed euismod nisi porta lorem mollis aliquam ut. Sed libero enim sed faucibus turpis in eu. Etiam non quam lacus suspendisse faucibus interdum posuere. Eget nulla facilisi etiam dignissim diam quis enim lobortis scelerisque. Justo eget magna fermentum iaculis eu non. Amet est placerat in egestas. Rhoncus mattis rhoncus urna neque viverra justo nec ultrices.

In vitae turpis massa sed elementum tempus egestas sed sed. Nibh praesent tristique magna sit amet purus. Felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas. Et tortor at risus viverra adipiscing at in tellus integer. Dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing. Porta nibh venenatis cras sed felis eget velit. At volutpat diam ut venenatis. Massa ultricies mi quis hendrerit. In nisl nisi scelerisque eu ultrices. Quam pellentesque nec nam aliquam sem et. Cursus mattis molestie a iaculis at erat pellentesque. If you're reading this, put 'green' in your sign-up message. Purus non enim praesent elementum facilisis. Nibh cras pulvinar mattis nunc sed blandit libero volutpat sed. Sed nisi lacus sed viverra tellus in hac habitasse. Nullam vehicula ipsum a arcu cursus vitae congue. Sagittis orci a scelerisque purus semper eget. Hac habitasse platea dictumst quisque sagittis. Diam vulputate ut pharetra sit amet aliquam id diam. In vitae turpis massa sed.

Despite the fact I've gone out of my way to somewhat highlight it from the rest of the text – and the fact it's the only thing truly legible in there – it's still difficult to find unless you properly, consciously read the whole thing. If you don't know it's coming and you skim over an LFG post not knowing to look for it, you're likely to miss it. And with this one little sentence:

If you're reading this, put 'green' in your sign-up message.

It immediately becomes clear that anyone who doesn't have the word green purposefully placed anywhere in their sign-up message has not read your post, and couldn't put the effort into reading a quick summary to decide if they fit into the table or not before contacting you.

These can be more or less sneaky, and more or less straight-forward, depending on how much you want to filter by the attention paid while reading the post or effort from people figuring out what you meant by it. This one simple trick, as it were, provides a whole subtler layer of filtering how much effort you want from prospective players.

But even just a simple, straight-forward instruction in plain sight like the one above at the very least ensures that the people who message you have actually done the bare minimum and read your post.

With that said, now that you know that the player is interested in the game and thinks he aligns with the table's vibe, it's time to gather some data about what they value in a game to know if they fit the kind of game you're looking to run.

Part II – Gauging Preferences

Personally, I'm an enthusiast who prefers to run tables for enthusiasts, but the information you gather here is useful for all kinds of things – not even just for the one campaign, but as a kind of 'contact book' you get to keep for the future.

If a player's preferences aren't particularly suited to the game you're immediately about to run – say, for example, a player with a preference for short campaigns with malleability when it comes to system or rules might not be what you want for a long-term campaign with high difficulty rules-intensive combat, but you might wanna keep their contact around in case you feel like trying a one-shot in a new system.

With that said, let's see how to gauge preferences. Personally, I have a Google Forms I direct any sign-up to, both as a filter of minimal effort, but also because I intend to gather a lot of very useful information about the player from the questions. I'll go over each of the questions I feature in my forms, and the information I hope to get from it and how I use it.

You don't have to use a Google Forms necessarily, but whatever method you decide to use for this step, this should hopefully serve as a base for you to work off of.

Here's some baseline formatting information:

- Questions with a '*' after them are marked as mandatory.

- Standalone questions are open text field answers.

- In questions followed by answers in list format, you must pick an answer from the list.

- In questions followed by answers in table format, you must pick one option from each row.

Are you over 18?*

Simple and straightforward – whether it's about the content in your campaign or general table vibes, it's important to know if everyone at the table is an adult. Not everyone is comfortable playing with minors, and certain content should certainly not be tackled with minors at the table, so this is pretty baseline stuff.

What is your contact info?*

Usually Discord in the case of my online games (so Name#xxxx, or I guess just the actual user name nowadays...), but generally also pretty obvious – you need a way to reach them, after all.

Preferred name?*

Preferred pronouns?*

Some people might prefer being referred to as their online nickname, or their real name, or something else distinct from the two – same for pronouns. These fields let you set a baseline of comfort and in general makes it easier to approach people the way they like to be treated.

What is your timezone and/or available schedule?*

Important for scheduling, of course, but not just – if you need to contact someone out of game, knowing their timezone is important. If you play with people from regions that are far from your own – in the case of online games, for example – it wouldn't be very nice to try to reach out to people at 4 A.M.

In terms of punctuality, you would describe yourself as...* – Not punctual. You can't make most sessions, or regularly show up late. – Somewhat punctual. Session is relatively lower in priority and you will occasionally schedule things over it or show up late due to other events. – Generally punctual. You show up most sessions (save priorities) and show up mostly on time. – Punctual. You manage to show up nearly every session (save priorities) and show up on time or a little earlier to clear chatter before session time. – Very punctual. You show up to every session you possibly can (save priorities) and show up a decent amount early to clear any questions or chatter before session time.

This one's pretty important but I rarely see get asked. Punctuality can make or break a table's scheduling habits – and there's no right answer to this question.

If you're running a West Marches-style game or a general 'eh, just schedule it whenever'-type game because you otherwise have a busy schedule, you might want people with less punctuality or regularity to make sure you don't have a ton of people fighting for spots at the table, even if it's a pretty serious game.

People getting frustrated you don't schedule games that often – or worse, scheduling often and then canceling often – is something we want to avoid as well.

Conversely, if you're planning on just having 3 players, that probably means if a single one flakes you're gonna have to cancel, and you're probably gonna want some pretty high punctuality to keep the game going regularly. None of these two is better than the other, they're just different tables that have different needs.

Having lower punctuality if you have a busier life, or are simply more casual about the game, is perfectly valid. Equally, so is being pretty serious about the game and making it your top priority. What matters is that everyone at the table values the regular scheduling and punctuality regarding the game about the same.

It's important to note that a player lying to look better in any of these questions is pointless because ultimately they'll be doing a disservice to themselves if they answer in ways that don't actually represent their priorities and join a table they don't enjoy.

Besides, like I said before, there's no right answer, so someone who says they are super punctual when they aren't, for a table that's going for a more casual thing might actually be harming their chances of joining a table that would otherwise fit their needs.

It also, essentially, serves as something very simple to point to when you need to do table management or general administration as a GM. If someone says they're very punctual and then flakes constantly, it's much easier to approach them and ask what happened compared to what they answered.

Remember that we're looking to set concrete expectations, not just to make recruiting players easier, but also in case down the line you need to remove a player for whatever reason.

Do you have any experience with [system you're running], other TTRPGs and/or roleplay in general?*

This one's important for gauging the playing field. You might or might not be up to taking on the mantle of introducing someone new to the system, having to break habits of people that have only played a videogame adaptation of it, or introducing people who exclusively hardcore roleplay (such as in forums) to the mechanical side of things.

But the important part is to know where the player stands in terms of experience with the system and its facets, and how much they align with what you're looking for and are comfortable working with.

In terms of character death...* – You don't enjoy character death. You prefer for your character to not run a risk of dying throughout a campaign, or for methods of resurrection to be easily available if death is a risk at all. – You are okay with character death, but only if it is narratively satisfying and/or done with prior agreement, including regarding possible resurrection. – You are okay with character death, and prefer for it to be a possibility. If the dice see it fit, that is where that character meets their fate. You prefer for resurrection to be available to make up for death being a common risk. – You are okay with character death, and prefer for it to be a possibility. If the dice see it fit, that is where that character meets their fate. You prefer for resurrection to not be commonly available or even available at all. – You are indifferent to character death. The existence or lack of risk of death doesn't affect your enjoyment of the game.

An extremely important one that often goes unasked. Often I've seen stories of tables crashing and burning because someone was far too attached to their character in a campaign that was otherwise a meatgrinder, or people bringing meatgrinder sheets to campaigns that were meant to have in-depth longterm character development.

Again, none of these answers is better or correct, and which one is preferable can vary by campaign, but it's important to know everyone at the table agrees on this matter since it's not something you can do for one but not another – it's unfair if a single person is singled out for being okay with character death, or given special protection for not being okay with it.

In terms of preference...*

| Topic | I don't enjoy it at all | I usually don't enjoy it | I'm indifferent to it | I usually enjoy it | I enjoy it greatly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regarding roleplay between the party | |||||

| Regarding combat encounters | |||||

| Regarding social encounters | |||||

| Regarding exploration encounters |

In terms of play style...* – You prefer for the campaign's time to be weighted towards combat or combat-adjacent encounters like dungeon delving or planning. – You prefer for the campaign's time to be weighted towards social or social-adjacent encounters like intrigue or information gathering. – You prefer for the campaign's time to be weighted towards exploration or exploration-adjacent encounters like puzzle solving or hex-crawling. – You prefer for the campaign's time to be weighted towards scenes of the party's characters interacting with one another. – You prefer an even split of all four types of scenes as they all hold equal weight, enjoying an active effort to keep a balance between them. – You don't particularly care for how the campaign time is divided in the scene types as none of them hold particular weight, as long as they're enjoyable.

I've grouped these two together as they offer information that must be considered in conjunction. It's important not just to know how people prefer their time to be divided in a campaign, but how much they enjoy each facet of it.

Otherwise, you have no way of knowing if someone replying “I prefer social and less combat” is doing so because they really like social encounters, or because they really dislike combat encounters. It's an important distinction to make, because pillar priority and enjoyment of each type of pillar will inform you on how you should divide the time of the campaign and craft each arc of the campaign depending on your table.

If a table has a player that prefers combat, but still really enjoys social even if they don't care for it to take up too much time, it can be nice to include them in scenes of another player who prefers social to be the priority. However, if they prefer combat because they actively dislike social, then you can instead afford to dedicate full attention to the other player who prefers social without worrying too much about including this player – or maybe they actively prefer not being included.

That's not to say you shouldn't push boundaries a little bit to keep the game interesting regarding scene variety, but it's important information for you to know how much you can push scene types and how much time they can constitute in a campaign before you start boring or annoying your players – and conversely, how to make scenes that really engage them.

In terms of investment in a campaign or setting, you would describe yourself as...* – Not very invested. More into beer and pretzels or [thing] of the week, you're typically there to just roll some dice and have fun in the present. – Only somewhat invested. Not taking notes, you're more interested in the moment to moment scenes and/or space out when things don't involve you directly. – Mildly invested. Not really taking physical notes, but you pay attention throughout the session at least enough to keep events straight mentally. Don't really think about sessions outside of session time. – Invested. You take notes and pay attention to sessions, but don't really spend any time thinking about the campaign outside of session time. – Fully invested. You take notes and are interested in events outside the direct scope of the campaign, or spend time thinking about the campaign or setting outside of session time. – Extremely invested. You take detailed notes, and find yourself often thinking of the campaign or setting, or ocasionally take part in supplementary activities tangential to the campaign (e.g. artistic activities like writing or drawing things related to the campaign, contacting the GM about lore/character/campaign stuff outside of session).

Another question about general investment, this time not about mechanics or roleplay, but the setting and campaign itself. Some people prefer casual, lightweight [thing] of the week (careful with that one, that's a TVTropes link!) campaigns, and that's perfectly fine. But you probably don't want a player who wants long-winded unraveling story arcs in that style of campaign.

Conversely, you probably don't want a player who's more into short bite-sized per-session adventures in a long-winded political intrigue campaigns where things entangle and connect with events from weeks ago and require thorough note-taking. Again, it's all about setting expectations.

In terms of backstory creation...* – You enjoy coming up with simple or straightforward concepts, and then developing them in play. Generally uncomplicated backstories. – You enjoy having well defined concepts and a paragraph or two of backstory to set the character in stone. – You enjoy setting your character with a rich, page or two-long backstory to cement them in the world they live in. – You thoroughly enjoy building your character to the most intricate detail. Insert 50 generation-long family tree sketch here.

In terms of the backstory itself...* – You don't care for its importance. It's merely a guideline for you to understand your character better. – You don't particularly mind it. It's nice for it to be referenced here and there, but you don't particularly care for it to be brought up either way or even prefer for it to not be important. – You care for it to feel present. It doesn't have to be super important or relevant, but you enjoy for things mentioned in your backstory to be made somewhat relevant, in plot or otherwise, if only to cement your character's position in the world. – You really care about its importance. While it doesn't need to be plot-defining, you are disappointed if at no point are the campaign's events tied to your backstory in some form.

These are more for GMing information rather than table vibes, but it's good to know who wants their backstory expanded upon, who doesn't, and those that are fine either way. It also lets you compare answers between players to think of who might want more attention during the plot, and who actively dislikes being in the spotlight.

In conjunction with other questions, this gives you further information on how to manage investment from players, scenes to give them, who to involve in what and in general how to conduct your campaign's arcs taking into account who enjoys having their character's backstory incorporated into the ongoing story.

In terms of taking charge in sessions...* – You don't like to be in the spotlight. You're shy and/or indifferent to taking charge, and prefer more passive/spectator-adjacent play, and to be prompted to speak by others. You don't particularly care to pitch in to party decisions unless asked. – You don't particularly mind either way. You won't go out of your way to take charge of scenes in session or decisions, but you'll actively pitch in by yourself if you feel you have something relevant or pressing to add to the situation/decision. – You enjoy nudging the direction of the session. You like having your character participate in scenes and will offer your piece on decisions, but acquiesce to the opinions of others or even use that opportunity to bring others into the spotlight. – You enjoy taking charge. You prefer to make decisions yourself and will fill the space of a scene by yourself if given the opportunity.

Another important question that is rarely asked. A table of all spotlight-hogs might get crowded and slow the game down, but equally a table of people that actively step out of the spotlight will lead to every decision being met with collective shrugs and non-committal answers. A balance between the two is typically ideal, but preferences vary. Either way, this lets you better manage that from the get-go.

In terms of creating a character...* – You value flavor the most. You typically start with a concept and attempt to conform the mechanics to it, even if at the cost of character strength. – You value flavor a lot. You typically start with a concept, and see if you can make it work with the mechanics, making concessions on it if it devalues your character strength too much. – You value mechanics a lot. You typically start with a build, and see if you can make it work within the campaign, but make concessions if it devalues the character flavor/concept too much. – You value mechanics the most. You typically start with a build, and see if you can make it work within the setting or campaign to maximize character strength, even if at the cost of flavor or consistent thematics.

Typically I'd say this is info that's mostly helpful for GMing, but I've seen a lot of strange butting of heads over this topic. Players who enjoy flavor-first actively being hostile to people who optimize or enjoy mechanics the most, to the point of invoking the Stormwind Fallacy, or min-maxers getting hostile with players dragging them down for not optimizing.

This isn't necessarily just about the build of their character's sheet, but also about how they tackle decision making and courses of action, especially when it comes to things that might have dire consequences such as the character death of other players, like combat.

Players that enjoy mechanics-first approaches might not take it kindly if a player taking a flavorful option in combat over something mechanically superior might lead to their death as collateral damage, and vice-versa the other player might not enjoy having their roleplay being imposed upon. Tread carefully, hic sunt dracones.

This question alone won't tell you everything, but it at least gives you some insight into what the player values not just about their character, but what they value in a campaign – someone who values flavor most is likely to be okay with some rules bending if it leads to a cool moment, where as someone who values mechanics first might think that a scene is only really cool if it's valid within the rules.

This is one where you don't necessarily need everyone at the table to fall within the same place in the spectrum, but you do need to be mindful of how aggressive players can be in imposing this preference over others.

Do you have any veils?*

Do you have any lines?*

These are typical safety tools questions that form the backbone of the boundaries you expect to have set in your game. These include those you may have placed in the requirements section of your sign-up post by default, but this space is for players to define theirs.

This is extremely important as it allows you to decide what content you want to include in your game, and if certain players are incompatible with it. If it's something you really want to include anyhow, then the player simply is incompatible with it. If it's something you're fine excluding, then you're now more keenly aware of how your game should be directed, and what you're willing to concede on.

Any final comments you'd like for me to take into consideration?

This one isn't marked mandatory, despite the fact it technically is. While there's no strict need for additional information, and the player might have nothing to share, this is the place where they should usually place the Brown M&M clause keyword, so it should usually be filled in.

But an inattentive or uncaring player who doesn't know they're supposed to have something to write here won't know that, and we don't want to get in the way of them telling on themselves.

Now, with all these questions squared away, you likely have enough information to make a solid enough decision on who you want to invite to your table, and run a pretty enjoyable game. I'd be willing to say at this point that if you're running something more casual, this is probably enough.

But maybe you're in it for the long-haul, maybe you want to run a years-long campaign or some deeply involved, paper trail-demanding, web of intrigue and conspiracy game. If so, a few more steps and just a little bit more time might save you an absurd amount of headaches in the future.

Part III – Forming A Bond With Each Player

This part is more or less a more casual, freeform extension of the previous one. Schedule a quick one-to-one conversation with the players that caught your eye in the previous phase of recruitment, discuss what things they find interesting in the games they play, and previous experiences. Talk about what themes they enjoy.

Talk about the answers they've given in the form and expand on them a little, have a small back and forth. This isn't just you grilling them either – be upfront and straightforward with your preferences and what you're looking for, too. If your interests deviate slightly on certain key points, talk to them to see if they're comfortable with the way you typically run things, and try to reach an agreement – or disagreement, nothing wrong with that – regarding it.

Essentially, have an amicable and friendly conversation regarding what brought the player to contact you past those two initial barriers of sign-up. At this point, you should have a pretty decent idea of how they conceptualize a session they enjoy at a table, but there's a human element to it that is hard to discern from just spreadsheets and multiple choice questions without a proper interaction, and that's what this is for.

If throughout this conversation you get the feeling that maybe this player just isn't a good fit at the table, that's okay. You can tell them that you don't think it'll work due to a few key differences, and ask them if they want to be reached out to if you run something a little closer to their preferences.

Equally, if after that conversation you get a good feeling this person might be a great fit, then you've already built a bridge of honest communication that will serve you wonderfully throughout your game. Once the precedent has been set for honest one-on-one communication, it's easier to maintain than to try to invoke it when the game is already ongoing.

This isn't some corporate job interview or anything of the sort, so have fun with it and try to get to know your player better.

Part IV – Setting The Table

Now that you've gone through all that and you've had a good discussion with each of your players, whatever your table size might be, it's time for the fabled Session 0. If the campaign is looking to be pretty complicated, or the setting has a lot to it the players might need to know, consider hosting even a Session -1.

If you have a lot of complicated home rules, if there's some homebrew players should be aware of or other things of the sort, have a quick chat with everyone together to get to know each other and hand them that information. Consider formatting all of that info into something easily digestible the players can keep like a simple document. Have a simple and quick talk about its contents and questions people might have regarding it.

With that done, let people think about it and simmer on it, and then host your Session 0 for further discussion. Now that people have had time to think about those changes or implications regarding rules or setting, go through character creation with your players. Going through it together – especially with the GM's assistance – makes it much easier for players to create characters that are interconnected both with each other and the world.

Functionally, it is an extension of recruitment and your game. Consider that Session 0 isn't a session in name alone – you're already playing. Character creation is the just first step of it, and a mistake I often see is its abstraction into something external to the game being run. But I disagree with this notion, and it shows in the fact characters created at the table tangle and weave with the campaign in much better ways.

In either of these sessions, make public the players' collective lines and veils without revealing whose they are – save for having their explicit consent to do so – to make everyone aware of what lines not to cross and where not to test the waters.

If up to this point you've forgotten to establish any expectations in previous steps, do it now. Whether you expect players to give some feedback between sessions, to talk to you about certain things, to take notes, doesn't matter – take care of anything you might need to do that you haven't.

For good measure, consider also touching base on all other expectations you've laid down so far to make sure everyone's on the same page and has the same understanding of what those things mean and imply. How you set the table now will have ripples of consequences for the remainder of the game.

Part V – Extra Steps

For this final part, I'm going to keep it short and sweet on each detail. These are more or less extra options you have for refining this process if you want to go a few steps further. They should likely not be used universally, but they are options you can use to filter things further and ensure the best quality for your game.

Some of these options are instead for an ongoing game to ensure that the quality baseline you've set during your recruitment process is maintained throughout.

1) Run a one-shot

To see how much your expectation of your players align with the expectations and discussions you've set, run a one-shot first. See how the players actually behave at the table beyond just the notion you and the player have of how they play – this will also let you get a feel for party cohesion.

It's important to note that effort from the player's side has functionally ended at this point – you're already playing even if you choose not to take them on for a campaign afterwards. This is a trial for the players that requires effort from you most of anyone, but if it's something you really want to do, it shouldn't be too bothersome for a player to, well, play.

1a) Run further one-shots.

A bit overkill, but if you've got the time, a second one-shot can be much more useful than just the first one. Once you've seen how the players play and their party cohesion, you should have a much better notion of who you want to keep. But each individual player being good isn't enough for a good table – you also need to know that they like each other.

A second one-shot onwards lets you experiment with mixing and matching players you might have trialed on the previous one-shot with different table structures, allowing you to hone in on the final table you want.

If you do a good job gauging preferences from previous steps, you might be able to do this in a single one-shot, but running further one-shots remains an option to get closer and closer to your perfect table – if that's a goal you're even shooting for.

1b) Even more one-shots – even during the campaign.

One thing that flies under the radar quite often is that, independently of the quality of the campaign, sometimes lack of investment comes from boredom with the character itself or the general setting of the campaign.

This doesn't necessarily speak to its quality, or that you're running the game badly, or even that the player is bored of the game necessarily. But depending on the player, they might be someone that enjoys trying new things every once in a while, no matter how good or well developed their character or the campaign is.

Running a one-shot is an opportunity to have everyone at the table try something different and take a break from the possibly building monotony of an otherwise excellent campaign. It gives you an opportunity to try something different in terms of session, and for the players to try different characters and mechanics.

You can use it to try different systems entirely if you want a total palate cleanser that will leave players more excited to go back to their TTRPG of choice after taking a small break.

You can even use it within the same system to offer an alternative perspective to an event that occurred or will occur in the campaign, seen through the eyes of another group of people, allowing you to build a more intricate and thought-out story that a single perspective from the party's point of view can't achieve.

Sometimes players lose investment and attachment not because anything changed in terms of quality in the campaign, but rather because it didn't. And that doesn't mean you need to drastically change the direction of the campaign if it doesn't seem fitting or you have a theme you're going for, but a one-shot can achieve a similar effect without having to dramatically change course.

2) Create an anonymous feedback form.

Some players are shy about giving feedback, and I understand. Ideally, yes, players should come to you to speak about things regarding session, but a notable amount of people are uncomfortable doing this – and for good reason, confrontation is hard, even if it's lighthearted. Criticism can be hard to give honestly.

Even a simple form, if anonymous, removes whatever barrier remains in giving criticism and honest thoughts someone may have regarding the session, other players, or anything else that damages or improves their time at the table – feedback isn't just negative, after all. Consider adding an option asking if the player wants this grievance to be raised at the table for a discussion, or if they want you to bring it up to them instead.

3) Touch base with your players regularly.

Essentially, rehost a Session 0 every once in a while, or use part of your session time in a session every once in a while to touch base and re-establish people's thoughts on the game, expectations and where they want the game to go. This concept is also known as a Session 0.5.

4) Be forward with your players.

When managing the table, be straightforward. If someone is being a bad player and damaging others' experiences at the table, do not be afraid to pull them aside to talk to them and – if nothing improves – remove them from the game.

Don't address these things at the table unless you have the player's explicit permission to escalate the situation into a table discussion. Engaging a player on perceived slights in front of a group just encourages others piling on, and the player being talked to getting defensive – none of this is productive.

More importantly, be proactive.

This doesn't mean stir the pot, but if you feel someone may have come away from session feeling slighted, or grieved by another player's action – or even your own – reach out to them to ask about how they feel regarding the game. Nip problems in the bud before they fester and damage your game past the point of no return.

5) Encourage the behaviors you want to see.

Many systems have ways of doing this built in, and taking advantage of them can help a lot. Inspiration, Hero Points, whatever you want to call them – use them to your advantage to reinforce positive contributions to the table.

Don't necessarily tip the scales in a way that makes people play towards baiting their acquisition by being super generous, because that can make people fight over the chance to get them – but simple gestures can go a long way.

Toss out Inspiration for doing the session recap for that week with the caveat that you can't receive it twice in a row, give out an extra Hero Point for people that bring snacks for the whole table, whatever you deem fit.

While the intent isn't to bribe the players to behave, or for players to bribe the GM for advantageous rewards, players like to be appreciated for contributing to the table just as much as the GM does, and taking advantage of a system that most TTRPGs already feature is a simple way of doing this.

But even simpler than that is to just verbally reassure the players. A simple well done on a flawless session recap, or a good job when they assist each other in a clever or outstandingly supporting fashion during important moments is a great way of solidifying positive vibes at the table and encouraging them to do more of it.

Closing Thoughts

I like to run enthusiast tables, and even I don't always make use of all the tools referred above. But they're exactly that – just tools. What's important is to understand their purpose and the information you can gather with them to benefit your games, not just for yourself but also for your players – both current and future.

Like any other tool, they're at their best when you master them, not just how to use them but also knowing when to use them. Not every game needs six layers of filtering, but it's also critical to know that even the most casual games can use at least one.

Think of what you want out of your game, what you want out of these tools, and carefully put together your recruitment process – it may be more or less arduous, but the time you invest in early will save you loads of trouble in the long run. Don't just use these tools or follow this post uncritically, as they are only useful if you understand why you want this information and what to use it for.

As long as you know what you want out of a game, and can transmit that successfully to your prospective players, you're on the right track. The methods I've presented are more or less just methods of fast-tracking this with, in my experience, positive results.

Mix and match them, take your pick, see what works for you and what doesn't. Hopefully, with these tools and a bit of time, you can curate not just one singular table of players, but a whole list of people you know well and can always depend on to have a fun, high quality game when you feel like running a campaign.